EMBRACE WetBond

Gruben- & Fissurenversiegler

Embrace WetBond Pit & Fissure Sealant zeichnet sich durch seine Fähigkeit aus, sich mit dem feuchten Zahn zu verbinden, durch seine Versiegelungsfähigkeit und seine Anpassung an die Zahnstruktur. Die Ränder sind nicht nachweisbar, und seine Fluoridaufladung

und der Langzeiterfolg sind in der Literatur beschrieben.1,2,3,4,5,6

Die Materialien enthalten kein Bisphenol A, kein Bis-GMA und keine BPA-Derivate.

EMBRACE ist seit 2002 im klinischen Einsatz und bietet Vorteile gegenüber herkömmlichen Füllungen:

- Verklebt mit dem feuchten Zahn

- Zahnintegrierend, randlos

- Eliminiert Mikroleckagen

- Fluoridaufladung

- Röntgenopak

Was ist EMBRACE Pit & Fissure Sealant?

Verbindung in feuchtem Mundmilleu

EMBRACE-Kunststoffe haften chemisch und mikromechanisch an leicht feuchten Zähnen.

Sie sind zahnintegrierend und schaffen eine randlose Schnittstelle zwischen dem Harz und dem Zahn, die Mikroleckagen eliminiert. So kommt es zu einer außergewöhnlichen Abdichtung gegen Mikroleckagen.

EMBRACE Pit & Fissure Sealant ist in drei Varianten erhältlich:

- als Naturton-Farbe

- als off-white Shade-Farbe

- als Low-Fill

Look & Feel von EMBRACE

Amber Auger zeigt auf der Chicago Midwinter Show wie EMBRACE Sealant im leicht feuchten Behandlungsgebiet am Zahnmodell angewendet wird.

Wirkprinzip von EMBRACE

EMBRACE ist hydrophil

Das patentierte, feuchtigkeitsfreundliche und ionische Harz hat dadurch die Grundvoraussetzung für bioaktives Potential, da alles Leben auf Wasser angewiesen ist.

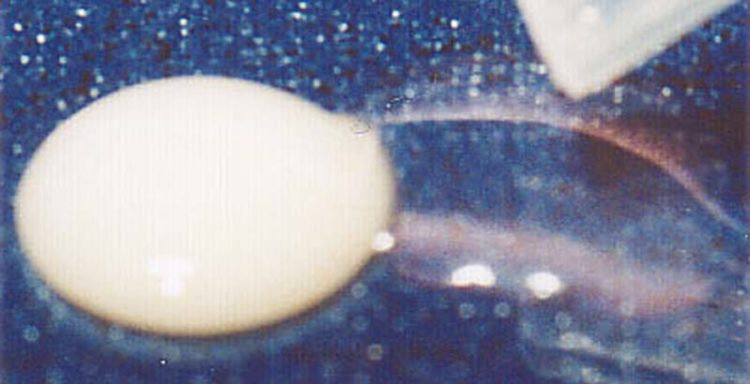

Wie man auf Abbildung 1 und 2 sehen kann reagiert EMBRACE wasserfreundlich und mischt sich sogar mit Wasser. Tatsächlich aktiviert Feuchtigkeit die Chemie des Embrace-Kunststoffs, sodass er sich besser mit der Zahnstruktur verbinden kann.

Eine kontrollierte und relativ geringe Wasseraufnahme ist vorteilhaft für bioaktive Materialien, die Wasser benötigen, um ihre bioaktiven Eigenschaften und ihr Potenzial für den Ionenaustausch freizusetzen. Eine übermäßige Wasseraufnahme kann jedoch die physikalischen Eigenschaften von Restaurations- und Basis-/Linermaterialien mit der Zeit beeinträchtigen.

EMBRACE wird auch in der Materialmatrix anderer PULPDENT Produkte wie der ACTIVA Serie eingesetzt. Die Wasseraufnahme von ACTIVA BioACTIVE-RESTORATIVE ist hier aber deutlich geringer als bei Glasionomeren und RMGIs und etwas höher als bei Kompositen, welche wiederum hydrophob und nicht bioaktiv sind

Abb. 1 Ein Wassertropfen wird neben den unausgehärteten Embrace-Kunststoff gelegt

Abb. 2 Embrace vermischt sich mit dem Wasser

Außergewöhnliche Randintegrität

Der herausragende Vorteil dieser zahnintegrierenden Technologie ist, dass sie „Rand-frei“ ist.

Nach dem Aushärten kann der Kliniker den Rand weder sehen noch mit einem Explorer finden. Beim Recall-Besuch kommt es zu keiner Verschlechterung des Komposits am Rand.

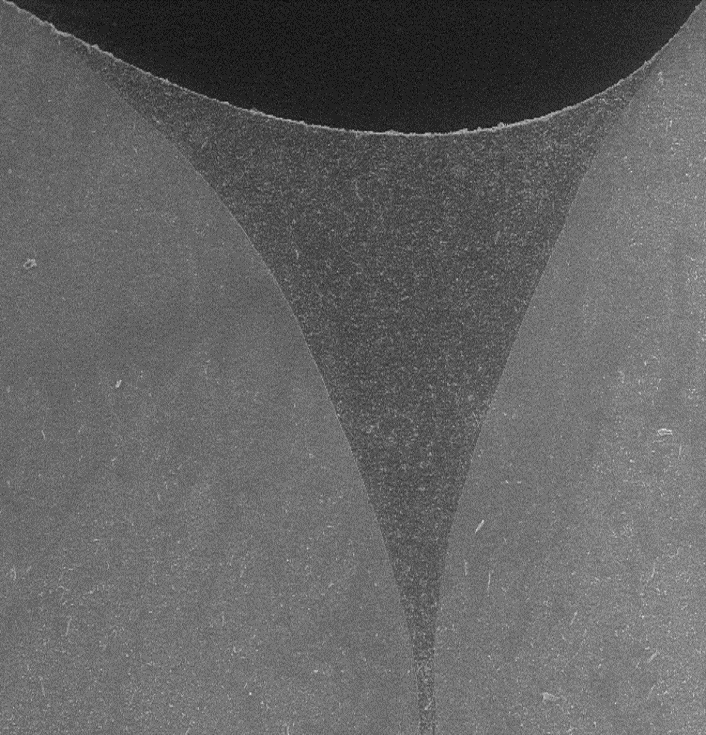

- Bild 1:

SEM zeigt Embrace Pit & Fissure Sealant ohne Haftvermittler. Beachten Sie den glatten Rand und die außergewöhnliche Anpassung des Versieglers an den Zahn. - Bild 2:

Das REM zeigt den traditionellen Gruben- und Fissurenversiegler des führenden Wettbewerbers ohne Haftvermittler. Beachten Sie den großen Spalt zwischen dem Versiegler und dem Zahn.

Kane B, Karren J, Garcia-Godoy C, Garcia-Godoy F.

Sealant adaptation and penetration into occlusal fissures.

Am J Dent 2009;22(2):89-91.

EMBRACE ist Lichthärtend und Röntgenopak

Physikalische Eigenschaften

EMBRACE Wetbond Pit & Fissure Sealant

Eigenschaften | Wert |

|---|---|

Photopolymerisationszeit | 20 sec |

Druckfestigkeit | 240 MPa |

Diametrale Zugfestigkeit | 43,4 MPa |

Prozentuale Löslichkeit | 0,06 % |

Literaturverweise

- Fluoride ion release and recharge over time in three restoratives. Slowikowski L, et al. J Dent Res 93 (Spec Iss A): 268, 2014 (www.iadr.org).

- Zmener O, Pameijer CH, Hernandez S. Resistance against bacterial leakage of four luting agents used for cementation of complete cast crowns. Am J Dent 2014;27(1):51-55.

- Zmener O, Pameijer CHH, et al. Marginal bacterial leakage in class I cavities filled with a new resin-modified glass ionomer restorative material. 2013.

- Flexural strength and fatigue of new Activa RMGIs. Garcia-Godoy F, et al. J Dent Res 93 (Spec Iss A): 254, 2014 (www.iadr.org).

- Deflection at break of restorative materials. Chao W, et al. J Dent Res 94 (Spec Iss A) 2375, 2015 (iadr.org).

- McCabe JF, et al. Smart Materials in Dentistry. Aust Dent J 201156 Suppl 1:3-10.

- Cannon M, et al. Pilot study to measure fluoride ion penetration of hydrophilic sealant. AADR Annual Meeting 2010.

- Water absorption properties of four resin-modified glass ionomer base/liner materials. (Pulpdent)

- pH dependence on the phosphate release of Activa ionic materials. (Pulpdent)

- Kane B, et al. Sealant adaptation and penetration into occlusal fissures. Am J Dent 2009;22(2):89-91.

- Rusin RP, et al. Ion release from a new protective coating. AADR Annual Meeting 2011.

- Sharma S, Kugel G, et al. Comparison of antimicrobial properties of sealants and amalgam. IADR Annual Meeting 2008.

- Naorungroj S, et al.Antibacterial surface properties of fluoride-containing resin-based sealants J Dent 2010.

- Prabhakar AR, et al. Comparative evaluation of the length of resin tags, viscosity and microleakage of pit and fissure sealants – an in vitro scanning electron microscope study. Contemp Clin Dent 2011;2(4):324-30.

- Pameijer CH. Microleakage of four experimental resin modified glass ionomer restorative materials. April 2011.

- Microleakage of dental bulk fill, conventional and self-adhesive composites. Cannavo M, et al. J Dent Res 93 (Spec Iss A): 847, 2014 (www.iadr.org).

- Comparison of Mechanical Properties of Dental Restorative Material. Girn V, et al. J Dent Res 93 (Spec Iss A): 1163, 2014 (www.iadr.org).

- Mechanical properties of four photo-polymerizable resin-modified base/liner materials. (Pulpdent)

- Singla R, et al. Comparative evaluation of traditional and self-priming hydrophilic resin. J Conserv Dent 2012;15(3):233-6.

- Water absorption and solubility of restorative materials. (Pulpdent)

- Increasing the Service Life of Dental Resin Composites. www.nidcr.nih.gov. grants & funding. concept clearances. May 2009.

- Spencer P, et al. Adhesive dentin interface the weak link in the composite restoration. Am Biomed Eng 2010;38(6):1989-2003.

- Murray PE,et al. Analysis of pulpal reactions to restorative procedures, materials, pulp capping, and future therapies. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2002;13:509.

- DeRouen TA, et al. Neurobehavioral effects of dental amalgam in children a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2006;295(15):1784-1792.

- Nordbo H, et al. Saucer-shaped cavity preparations for posterior approximal resin composite restorations observations up to 10 years. Quintessence Int 1998;29(1):5-11.

- Skartveit L, et al. In vivo fluoride uptake in enamel and dentin from fluoride-containing materials. J Dent Child 1990; 57(2):97-100.

- Wear of a calcium, phosphate and fluoride releasing restorative material. Bansal R, et al. J Dent Res 94 (Spec Iss A): 3797, 2015 (iadr.org).

- Wear resistance of new ACTIVA compared to other restorative materials. Garcia- Godoy F, Morrow BR. J Dent Res 94 (Spec Iss A): 3522, 2015 (iadr.org)

- Pameijer CH, Garcia-Godoy F, Morrow BR, Jeffereis SR. Flexural strength and flexural fatigue properties of resin-modified glass ionomers. J Clin Dent 2015;26(1):23-27.

- Pameijer CH, Zmerner O, Kokubu G, Grana D. Biocompatibility of four experimental formulations in subcutaneous connective tissue of rats. 2011.

- Pameijer CH, Zmener O. Histopathological evaluation of an RMGI ionic-cement [Pulpdent Activa], auto and light cured – A subhuman primate study. 2011.

- ACTIVA BioActive-Restorative: 6-month clinical performance. The Dental Advisor 2015. www.dentaladvisor.com.

- ACTIVA BioActive-Restorative: One-year clinical performance +++++. The Dental Advisor 2015. www.dentaladvisor.com.

- Compressive strength and deflection at break of four cements. Daddona J, Pagni S, Kugel G. J Dent Res 95 (Spec Iss A) 0658, 2016 (iadr.org).

- Surface deposition analysis of bioactive restorative material and cement. Chao W, Perry R, Kugel G. J Dent Res 95 (Spec Iss A) S1313, 2016 (www.iadr.org).

- Comparison of compressive strength of liner materials. Epstein N, et al. J Dent Res 95 (Spec Iss A) S0653, 2016 (www.iadr.org).

- Water absorption and solubility of four dental cements. Hall J, et al. J Dent Res 95 (Spec Iss A) S1126, 2016 (www.iadr.org).

- Shear bond strength of several dental cements. Tran A, et al. J Dent Res 95 (Spec Iss A) S0579, 2016 (www.iadr.org),

- Repetitive deflection strengths of adhesive cements. Samaha S, et al. J Dent Res 95 (Spec Iss A) S1076, 2016 (www.iadr.org).

- Fluoride release of bioactive restoratives with bonding agents. Murali S, et al. J Dent Res 95 (Spec Iss A) S0368, 2016 (www.iadr.org).

- Profilometry bioactive dental materials analysis and evaluation of dentin integration. Garcia-Godoy F, Morrow BR. J Dent Res 95 (Spec Iss A) 1828, 2016 (iadr.org).

- Staining and whitening products induce color changes of multiple composites. Parks H, Morrow BR, Garcia-Godoy F. J Dent Res 95 (Spec Iss A) S1323, 2016 (www.iadr.org).

- Profilometry based composite abrasion using different current dentifrices. Lindsay AA, Morrow BR, Garcia-Godoy F. J Dent Res 95 (Spec Iss A) S0318, 2016 (iadr.org).

- Bansal R, Burgess JO, Lawson NC. Wear of an enhanced resin-modified glass-ionomer restorative material. Am J Dent 2016;29(3):171-174.

- Evaluation of pH, fluoride and calcium release for dental materials. Morrow BR, Brown J, Stewart CW, Garcia-Godoy F. J Dent Res 96 (Spec Iss A) 1359, 2017 (iadr.org).

- Adhesion of s. mutans biofilms on potentially antimicrobial dental composites. Mah J, Merritt J, Ferracane J. J Dent Res 96 (Spec Iss A) 2560, 2017 (iadr.org).

- Microleakage under class ll restorations restored with bulk-fill materials. Kulkami P, et al. J Dent Res 96 (Spec Iss A) 2604, 2017 (iadr.org).

- Fluoride release of dental restoratives when brushed with fluoridated toothpaste. Epstein N, Roomian T, Perry R. J Dent Res 96 (Spec Iss A) 1254, 2017 (iadr.org).

- ACTIVA Bioactive-Restorative. Two-year clinical performance +++++. The Dental Advisor 2017, dentaladvisor.com.

- May E, Donly KJ. Fluoride release and re-release from a bioactive restorative material. Am J Dent 2017;30(6):305-308.

- Garoushi S, Vallittu PK, Lassila L. Characterization of fluoride releasing restorative dental materials. Dent Mater J 2018;37(2):293-300.

- Reznik J, Kulkarni P, Shah S, Chang B, Burgess JO, Robles A, Lawson NC. Crown Retention Strength and Ion Release of Bioactive Cements. J Dent Res 97 (Spec Iss A) 656, 2018 (iadr.org).

- Boutsiouki C, Lücker S, Domann E, Krämer N. Is a bioactive composite able to inhibit secondary caries. Justus-Liebig-Universitat Giessen, Vaterstetten. Germany 2017.

- Alrahlah A. Diametral tensile strength, flexural strength, and surface microhardness of bioactive bulk fill restorative. J Contemp Dent Practice 2018;19(1):13-19.

- Influence of novel bioactive materials on dentinal enzymatic activity. Comba A, Breschi L, et al. J Dent Res 97 (Spec Iss A) 0273, 2018 (iadr.org).

- Dentifrices, surface roughness and depth loss of restorative materials. Smith JB, Lambert AN, Morrow BR, Pameijer CH, Garcia-Godoy F. J Dent Res 97 (Spec Iss A) 1621, 2018 (iadr.org).

- Enamel demineralization adjacent to orthodontic brackets bonded with Active Bioactive Restorative. Saunders KG, Donley KJ, Mattevi G. of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio 2017.

- Bioactive materials, demineralization, and shear strength of orthodontic brackets. Donohue J, et al. J Dent Res 96 (Spec Iss A) 3289, 2017 (iadr.org).

- Roulet J-F, et al. In vitro wear of two bioactive composites and a glass ionomer cement. DZZ International 2019;1(1):24-30.

- Banon R, et al. Clinical evaluation of a new bioactive ionic resin material (ACTIVA™ BIOACTIVE) in primary molars – a split mouth randomized trial. Ghent University 2018.

- Omidi BR, et al. Microleakage of an enhanced resin-modified glass ionomer restorative material in primary molars. Researchgate 2018;15(4)205-213.

- Croll TP, Lawson NC. Activa Bioactive-Restorative material in children and teens: examples and 46-month observations. Inside Dentistry 2018.

- Sauro S, et al. Effects of ions-releasing restorative materials on the dentine bonding longevity of modern universal adhesives after load-cycle and artificial saliva aging. Materials 2019;12:722.

- Lloyd VJ, Hunter F, Comisi J. The bio-mineralization potential of various bioactive restorative materials, MUSC 2019.

- Bhadrad, et al. A 1-year comparative evaluation of clinical performance of nanohybrid composite with Activa bioactive composite in Class II carious lesion: randomized control study. JCD 2019;22(1):92-96.

- Maciak M. Novel applications of a bioactive resin in perforations, root resorption and endodontic-periodontic lesions. Roots 2018;14(4):32-36.

- ElReash A, et al. Biocompatibility of new bioactive resin composite versus calcium silicate cements – an animal study. BMC Oral Health 2019;19:194-203.

- Alkhudhairy F, et al. Adhesive bond integrity of dentin conditioned by photobiomodulation and bonded to bioactive restorative material. Photodyagn Photodyn 2019;28:110-113.

- Lopez-Garcia S, et al. In vitro evaluation of the biological effects of ACTIVA Kids BioACTIVE Restorative, Ionolux, & Riva LC on human dental pulp stem cells. Materials 2019,12,3694;doi:10.3390/ma12223694.

- Jun SK. The biomineralization of a bioactive glass-incorporated light-curable pulp capping material using human dental pulp stem cells. Biomed Res Int 2017;doi.org_10.1155_2017_2495282.

- Abdulla HA, Majeed MA. Assessment of bioactive resin-modified glass ionomer restorative as a new CAD CAM material. Part 1_marginal fitness study. Indian J Foren Med Tox 2020;14(1)865-870.

- Abdulla HA, Majeed MA. Assessment of bioactive resin-modified glass ionomer restorative as a new CAD CAM material part ll_fracture strength study. J Res Med Sci 2019;7(5)_74-79.

- Sauro S. et al. Effects of ion-releasing restorative materials on dentine bonding longevity of modern universal adhesives after load-cycle and artificial saliva aging. Materials 2019;12(5)722.

- Karabulut B, et al. Reactions of subcutaneous connective tissue to MTA, Biodentine, and a newly developed base-liner. Wiley 2020;doi.org_10.1155_2020_6570159.

- Awad MM, et al. Influence of surface conditioning on the repair strength of bioactive restorative material. J Appl Biomater Func 2020;18.

- Bishnoi N, et al. Evaluating marginal seal of a bioactive restorative material Activa Bioactive and two bulk fill composites in class ll restorations-an in vitro study. Int J Appl Sci 2020;6(3)98-102.

- Rouler J-F, et al. In vitro wear of dual-cured bulkfill composites and flowable bulkfill composites. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2020;1–9.

- Pires PM, et al. Contemporary restorative ion-releasing materials_ current status, interfacial properties and operative approaches. Brit Dent J 2020;229(7)450-458.

…weitere Literatur finden Sie auf unserer vollständigen Literaturliste…